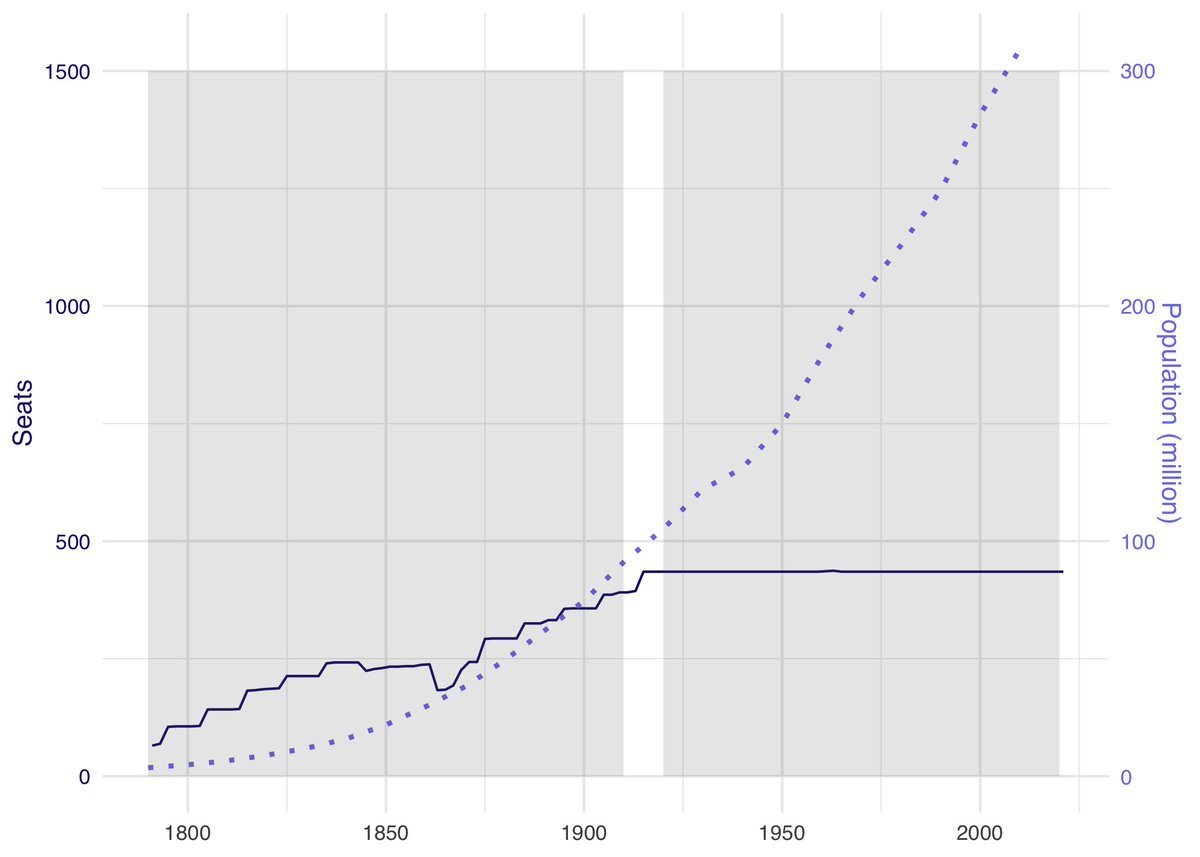

Have you ever considered your representation? There are fifty senators in the Senate, two representatives per state. Have you ever wondered why we have 435 representatives in the House? The Constitution instructs Congress to reapportion the members of the House every ten years after the census. So, why has it been 435 for so long?The history goes like this…Between 1920 and 1929, while Americans adjusted to a rapidly expanding economy and population, returning from war, and were taxed to pay for the debt, Congress failed to apportion the House due to political disputes over urban vs. rural representation. And then quietly capped the people’s power, passing the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929 and limiting representation in the House to 435 seats. While the number was adequate for 1929, the population has tripled to nearly 330 million. In 1929, each House member represented 220,000 people; today, that number is about 750,000. As the population grew while representation remained capped, the people's power was diluted.The chart above shows the growth of the population and representation in America. Notice how the population and representation grew together until 1911.

The House's capping and the increase in population have shrunk our republic, making it ripe for corruption and control. With fewer representatives, elections become more expensive, lobbyists gain more influence, and the average citizen's voice gets drowned out. Thus, the House becomes a place for a wealthy and exclusive political class instead of a place for the people.History’s greatest political struggles have centered on one issue: representation. Anytime a government fails to live up to its stated purpose, friction between the political elite and everyday commoners abounds. The fight is over who should be in charge. And how much power they should have. Different parties and interests grasp for power, shifting wealth and influence in a different direction. The story of civilization is a story of expanding and restricting representation, and America is no exception.And yet, today, we seem to have forgotten the central issue. Right now, there are educated and decent people trying to have real discussions about representation, but most Americans can’t hear them over all the noise—the endless partisan fights, the power grabs, the culture wars. Red and Blue say they speak for "the people," but neither is talking about the people's actual power: representation. Both sides are fighting to save democracy, and neither is protecting republicanism.To be an American and protect our freedom, we must understand representation. The American Revolution was just another chapter in this long struggle. Its battle cry—"No taxation without representation"—wasn’t just about taxes; it was about representation. About who has a voice in government. The colonists didn’t see themselves as mere subjects of a distant king; they saw themselves as free people who deserved a say in their own laws. They saw themselves as Republicans and they fought for representation. Being a republican wasn't about belonging to a party but supporting representative government. The American Revolution was the next step in a centuries-old process. From the Magna Carta to the Glorious Revolution, English history had already laid the groundwork for the idea that rulers must answer to the governed. The American Revolution carried that tradition forward, demanding a system where power came from the people—not the monarchy.Representation didn’t stop expanding after America declared independence. The biggest political battles in U.S. history centered around who gets included in the promise of self-government. The Great Compromise divided Congress between the Senate, representing the States, and the House, securing representation for the people of the states. The Three-Fifths Compromise was a fight over representation—slave states wanted more congressional seats without granting representation to enslaved people. The Civil War was, at its core, a war over whether the country would fully embrace the republican right of representation or continue a system where millions were governed without consent. Jim Crow laws in the South weren’t just about racial oppression; they were designed to strip Black citizens of their representation, even after the 15th Amendment granted them the right to vote.The women’s suffrage movement fought to expand representation again, culminating in the 19th Amendment. The Civil Rights Movement was another chapter, as activists like Martin Luther King Jr. demanded that America live up to its own ideals by ensuring that Black Americans had real political power. Every single one of these battles was about who gets a seat at the table and who gets left out. The Progressive Era reshaped American republicanism by expanding federal and executive power, shifting authority from states and local communities to the presidency. It also shifted how Americans thought about themselves—not as citizens in a republic but as beneficiaries of federal action—no longer citizens of a republic but members of a political party.The Progressive Era expanded democratic participation while also concentrating power in the federal and executive branches. Reforms like the 17th and 19th Amendments expanded voting rights, while initiatives and referendums gave citizens direct influence over laws. At the same time, federal agencies like the FTC and FDA centralized power in Washington, and presidents like Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson expanded executive authority through trust-busting and economic intervention. Americans now think of their government as a democracy to be won, rather than a republic to be represented. Our government divides, separates, and balances power. It vests the people's power into the House of Representatives, and our founders believed the right of representation was fundamental to a free society. After all, freedom is having a say in the rules.In fact, the 1st Congress proposed an amendment known as "Article the First," which aimed to establish a fixed ratio of people to Representatives. Although it was not ratified due to a flaw in its formulation, Congress continued to expand the House of Representatives after each census until 1920.Our Representative is like a customer service agent. They listen and inform. When we have a problem, they should listen to our concerns and inform us of a solution. Have you ever called customer service only to get stuck in an endless loop of automated responses? You ask for a representative, but you can’t reach one. It’s frustrating, isn’t it? You could visit the store, but they’ll likely direct you back to the phone line. The result? An unhappy customer and a company that loses business.Now, imagine this same problem in government. What happens when citizen representation is replaced by technology and outsourced to staff? How do people get their problems solved?Americans are frustrated with an unresponsive government. The solution isn’t more technology, more staff, or more bureaucratic layers—it’s more representatives. Uncapping the House is the most direct and effective way to restore meaningful representation and ensure that every voice is heard. The status quo isn’t working. It’s time to fix it by expanding the People’s House.